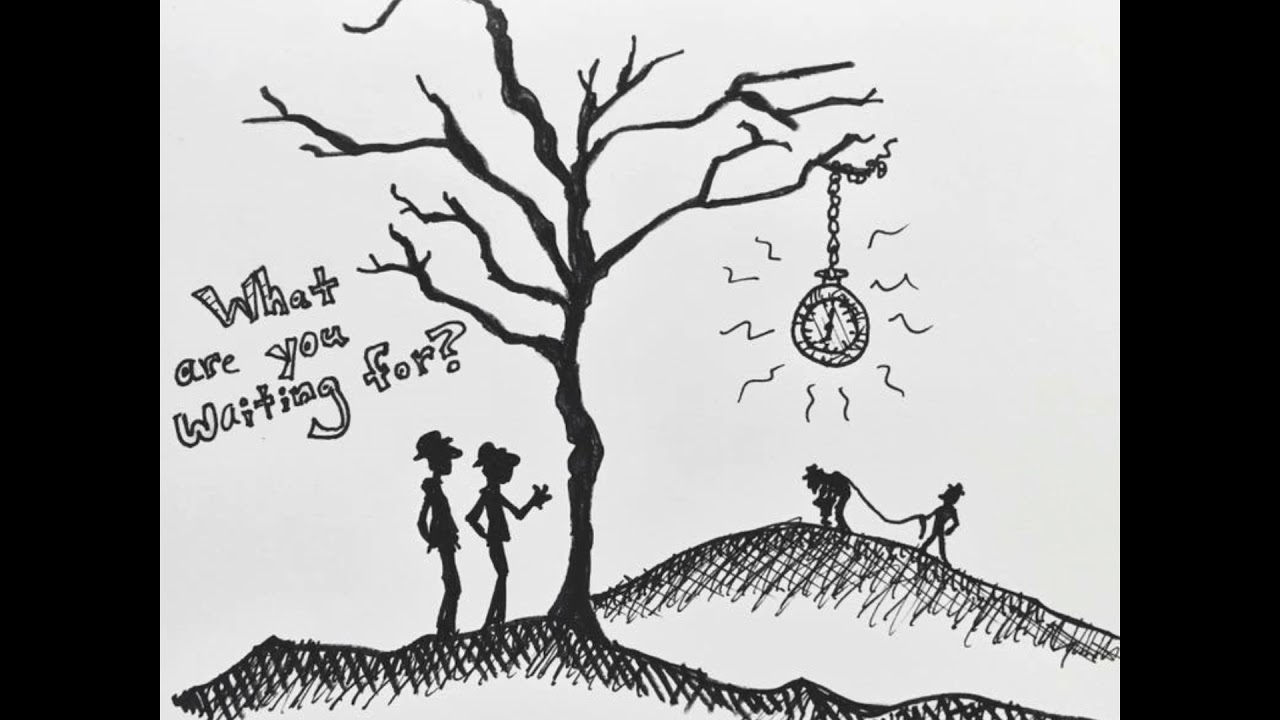

Demystified Videos In Demystified, Britannica has all the answers to your burning questions.Britannica Classics Check out these retro videos from Encyclopedia Britannica’s archives.When the French playwright Jean Anouilh saw the Paris premiere of the play in 1953, he described it as ‘ The Thoughts of Pascal performed by clowns’. In Camus’ essay, Sisyphus survives the pointless repetition of his task, the rolling of a boulder up a hill only to see it fall to the bottom just as he’s about to reach the top, by seeing the ridiculousness in the situation and laughing at it.)Īnd the discrepancy between what the play addresses, which is often deeply philosophical and complex, and how Beckett’s characters discuss it, is one of the most distinctive features of Waiting for Godot. (An important aspect of Camus’ ‘ Myth of Sisyphus’ is being able to laugh at the absurdity of human endeavour and the repetitive and futile nature of our lives – which all sounds like a pretty good description of Waiting for Godot. In this regard, comparisons with Albert Camus and existentialism make sense in that both are often taken to be more serious than they actually are: or rather, they are deadly serious but also alive to the comedy in everyday desperation and futility. Among Beckett’s many influences, we can detect, in the relationship and badinage between Vladimir and Estragon, the importance of music-hall theatre and the comic double act and vaudeville performers wouldn’t last five minutes up on stage if they indulged in pretentiousness. Waiting for Godot is a play which cuts through pretence and sees the comedy as well as the quiet tragedy in human existence. But it is clear that they are fairly well-educated, given their vocabularies and frames of reference.Īnd yet, cutting across their philosophical and theological discussions is their plain-speaking and unpretentious attitude to these topics. Precisely what social class Vladimir and Estragon come from is not known. The other well-known thing about Waiting for Godot is that Vladimir and Estragon are tramps – except that the text never mentions this fact, and Beckett explicitly stated that he ‘saw’ the two characters dressed in bowler hats (otherwise, he said, he couldn’t picture what they should look like): hardly the haggard and unkempt tramps of popular imagination. The key lies not so much in the what as in the how. So, what made Beckett’s play so innovative to 1950s audiences? And plays in which ‘nothing happens’ were already established by this point, with conversation and meandering and seemingly aimless ‘action’ dominating other twentieth-century plays. As Michael Patterson observes in The Oxford Guide to Plays (Oxford Quick Reference), the theme of promised salvation which never arrives had already been explored by a number of major twentieth-century playwrights, including Eugene O’Neill ( The Iceman Cometh) and Eugène Ionesco ( The Chairs). However, contrary to popular belief, this is not what made Waiting for Godot such a revolutionary piece of theatre.

It is always just beyond the horizon, in the future, arriving ‘tomorrow’. With this structure in mind, it is hardly surprising that the play is often interpreted as a depiction of the pointless, uneventful, and repetitive nature of modern life, which is often lived in anticipation of something which never materialises. The ‘action’ of the second act mirrors and reprises what happens in the first: Vladimir and Estragon passing the time waiting for the elusive Godot, Lucky and Pozzo turning up and then leaving, and the Boy arriving with his message that Godot will not be coming that day. Waiting for Godot is often described as a play in which nothing happens, twice. After Lucky has performed a dance for them, he is ordered to think: an instruction which leads him to give a long speech which only ends when he is wrestled to the ground. He eats a picnic, and Vladimir requests that Lucky entertain them while they wait for Godot to arrive. Pozzo tells them that he is on his way to the market, where he intends to sell Lucky. In order to pass the time while they wait for Godot to arrive, the two men talk about a variety of subjects, including how they spent the previous night (Vladimir passed his night in a ditch being beaten up by a variety of people), how the Crucifixion of Jesus Christ is described in the different Gospels, and even whether they should hang themselves from the nearby tree.Ī man named Pozzo turns up, leading Lucky, his servant, with a rope around his neck like an animal. The setting is a country road, near a leafless tree, where two men, Vladimir and Estragon, are waiting for the arrival of a man named Godot. The ‘plot’ of Waiting for Godot is easy enough to summarise.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)